This blog post consists of a collection of maps and graphs examining the changes in economic inequality throughout neighborhoods in New York City. The maps were inspired by Daniel Kay Hertz’s fantastic series of maps visualizing inequality in Chicago. See also my previous maps examining the change in income inequality in San Francisco. To create these maps and graphs, I used census block group data from the National Historical Geographic Information System.

Rising economic inequality has been well documented both in New York City and throughout the nation. This post takes a look at one specific consequence of that rise in inequality: the decline of middle-class neighborhoods in New York City. The map below visualizes this decline from 1990 to 2015. Middle-income areas are colored in light-grey, upper-income areas in shades of green, and lower-income areas in shades of red. Because this map is so large it can be hard to see changes in individual neighborhoods, so throughout the rest of this post are maps for each of the five boroughs of New York City.

In 1990, 40% of New Yorkers lived in middle-income areas, but by 2015 that number had dropped to 35%. This decline has not been uniform across NYC, but has instead varied widely between the five boroughs. Manhattan and The Bronx have seen many of their middle-class neighborhoods decimated, with less than 20% of their population residing in these areas by 2015. Queens and Brooklyn saw smaller, but still significant, declines in middle-class areas. Staten Island was the one borough to defy this trend, with a larger share of residents living in middle-class areas in 2015 than in 1990.

The share of New Yorkers living in upper-income neighborhoods increased during this period, going from 14% of the City’s population in 1990 to 18% in 2015. The number of people living in lower-income neighborhoods stayed relatively stable, at 46% in 1990 and 47% in 2015. However, once again these changes varied sharply between boroughs, with Manhattan and Brooklyn seeing large increases in the share of individuals living in upper-income neighborhoods, while Queens, The Bronx, and Staten Island have instead seen growth in lower-income neighborhoods.

This post will examine trends in neighborhood income inequality for each of the five boroughs, going in order of their population size. Brooklyn will start, followed by Queens, Manhattan, The Bronx, and finally Staten Island. A few conclusions and final thoughts follow. The methodology, which describes how lower-income, middle-income, and upper-income areas were defined and measured, is located at the bottom of this post.

Brooklyn

Of the five boroughs, Brooklyn’s neighborhoods are most representative of the city as a whole, at least in terms of income. There are still some notable differences however. 56% of the population lives in lower-income neighborhoods, which is 9 percentage points higher than the city as a whole. In contrast, only 11% of Brooklynites live in upper-income neighborhoods, compared to 18% for the entire city. The share of the population living in middle-income neighborhoods is very similar at 33% for Brooklyn vs. 35% for the City. Brooklyn has slightly poorer neighborhoods than the rest of the city, but this gap has declined over the past 25 years.

Since 1990 the share of Brooklyn residents living in upper-income neighborhoods has more than doubled, from 5% of the population in 1990 to 11% in 2015. This gain has come at the expense of both lower-income and middle-income neighborhoods. Interestingly, the growth of upper-income neighborhoods in Brooklyn has come entirely in the last 15 years. Between 1990 and 2000, the share of people living in upper-income neighborhoods was stable, as seen in the graph above. But after 2000 the population of upper-income neighborhoods rose sharply.

This rapid rise in the number of upper-income neighborhoods is tied to the gentrification of north-west Brooklyn. Neighborhoods such as Gowanus, Red Hook, Boerum Hill, and northern Williamsburg have undergone massive transformations in a relatively short period of time, going from lower-income or middle-income neighborhoods to some of the highest-income areas in the city. This transformation can be observed in the map above, as the red and grey areas between Park Slope and Manhattan disappear into a sea of green.

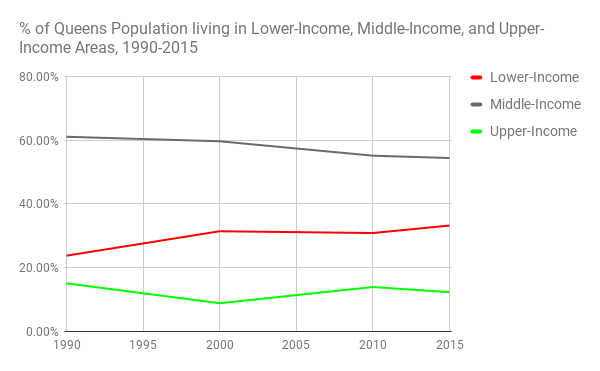

Queens

Queens is the most middle-class borough in New York City. Well over a million Queens residents live in middle-income areas, 54% of the borough’s total population. Still, a significant chunk of Queens’ population, 33%, live in lower-income areas. However, unlike other borough’s in the city, the majority of low-income areas in Queens have median incomes just on the edge of middle-class status. These neighborhoods could be thought of as “lower middle-class” or “working-class”. Likewise, the majority of upper-income areas in Queens are not super-rich, but instead have median incomes only slightly above middle-class status. Thus, very few neighborhoods in Queens are intensely rich or extremely poor, which suggests that income inequality in Queens is significantly lower than in the rest of the city.

Despite Queens’ relatively low levels of inequality, since 1990 it has still seen a decline of 7 percentage points in the proportion of it’s population living in middle-class neighborhoods. The percentage of the population living in upper-income areas has also declined by 3 percentage points. In their place, many more residents are living in lower-income areas, although as noted earlier these areas are usually not intensely impoverished. It may be that Queens has become a refuge for those priced out of other parts of New York City, which could explain this rise in the proportion of the population living in lower-income neighborhoods.

Neighborhoods in Queens have seen relatively subtle changes in income status over the past 25 years. One of the few changes visible in the map above is that lower-income areas around Flushing and Jamaica have grown in size. A more general change can also be seen throughout Queens, as large areas that had been almost entirely middle-income, such as Middle Village, Woodhaven, and Ozone Park, have seen bits and pieces of territory shift out of the middle-income category. These neighborhoods, after being almost entirely middle-income in 1990, became patchworks of low-income, middle-income, and high-income areas by 2015. Still, it is difficult to see many dramatic changes in these neighborhoods, especially compared to some of the neighborhood transformations in Brooklyn or Manhattan.

Manhattan

Manhattan’s neighborhoods look drastically different from the rest of the city. The borough is starkly divided between lower-income and upper-income neighborhoods, with very few middle-income neighborhoods in between. The share of residents living in upper-income neighborhoods is particularly large, at 47%. Of all New Yorkers who live in upper-income neighborhoods, more than half live in Manhattan, despite the borough having less than 20% of the total population of New York. This concentration of upper-income neighborhoods becomes even more stark when looking at extremely high-income neighborhoods, defined as those neighborhoods with a household median income over 200% of the metropolitan area median income (this translates to neighborhoods with a median income of over $137,500 dollars in 2015). Over 80% of the New Yorkers living in these extremely high-income areas reside in Manhattan.

By 1990 Manhattan already had a much smaller number of middle-class neighborhoods compared to the other boroughs, but even these few middle-class neighborhoods have shrunk rapidly. 29% of residents lived in middle-income areas in 1990, but by 2015 the number had dropped to 18%. Likewise, the share of the population living in low-income areas dropped from 47% to 35%. The share of the population living in upper-income areas has skyrocketed, and is well on it’s way to becoming a majority within the next few years.

Those middle-income areas that remain are mostly positioned as thin buffers between intensely high-income and intensely low-income areas, such as a few blocks located between Midtown and the Lower East Side, or middle-class pockets wedged between the Upper East/Upper West sides and Harlem. Middle-income neighborhoods that existed in 1990, including portions of the Upper West Side and Midtown, have rapidly transitioned into high-income areas. Lower-income areas around Washington Heights, Harlem, and the Lower East Side have all shrunk dramatically over the past 25 years. This dramatic transformation of Manhattan shows no signs of slowing down.

The Bronx

As of 2015, The Bronx has by far the largest number of people living in low-income areas compared to the rest of the city, at 77%. Additionally, 46% of the Bronx population lives in “extremely low-income” neighborhoods, defined as those where the median household makes less than 45% of the metropolitan area median income. In 2015, this meant that the median household income in “extremely low-income” areas was less than $31,000 a year. There are still some middle-income areas in the Bronx, but they only contain 18% of the population. A handful of upper-income areas contain another 5% of the population.

Since 1990, the number of individuals living in low-income areas increased by 8 percentage points, while the number living in middle-income areas dropped by 8 percentage points, and the number in upper-income areas remained stable. Nearly all of the jump in the number of people living in low-income areas occurred between 1990 and 2000. Since 2000 the low-income portion of the population has stayed flat, while the % of the population living in middle-income areas has slowly dropped and the % living in upper-income areas has slowly risen. This suggests that the already-small number of middle-class neighborhoods in the Bronx are in danger of shrinking even further.

The Bronx is starkly divided geographically, with the south-western portion of the borough composed almost entirely of low-income areas, while the eastern portion of the borough has more middle-income and high-income areas. There is also a pocket of high-income areas in the neighborhood of Riverdale in the north-west corner of the borough. Between 1990 and 2015, the main geographic change visible was the transition of some portions of the eastern section of the borough from middle-income to low-income. The neighborhood of Allendale is a good example of this, as in 1990 only the western edge of the neighborhood was low-income, wheareas by 2015 most of the neighborhood had transitioned. The western half of the borough remained more stable, with south-west neighborhoods like Belmont, Highbridge, and Mott Haven remaining solidly low-income, while Riverdale remained mostly high-income.

Staten Island

Staten Island’s neighborhoods have a very different income distribution from the rest of the city. Only 14% of Staten Island residents live in low-income neighborhoods, far lower than any other borough. 51% of the population lives in middle-income neighborhoods, second only to Queens, and 35% of the population lives in upper-income neighborhoods, second only to Manhattan. The island has a relatively low level of inequality compared to the rest of the city, and is generally on the wealthier side.

Not only is the current composition of Staten Island radically different from the rest of the city, but it has also been subject to very different trends. The broadest trend across the rest of the city has been a decline in the number of people living in middle-income areas, and an increase in the number living in high-income areas. In Staten Island, this trend has been reversed: The number living in middle-income areas grew by 12%, while the number living in high-income areas declined by 14%. It seems that incomes did not grow as quickly in Staten Island as in the rest of the city, meaning that many high-income areas slid back into middle-income status.

No Staten Island neighborhoods saw the dramatic swings in income that areas in Manhattan and Brooklyn saw. Even the more subtle changes seen in The Bronx and Queens are hard to pick out in Staten Island. One visible trend is that Southern Staten Island had been mostly green in 1990, but by 2015 the area had transitioned to a mix of upper-income and middle-income areas. Areas scattered across the island went from being light green, representing the lowest category of upper-income, to being grey for middle-income areas.

Conclusions:

New York City as a whole has seen a rise in upper-income neighborhoods, and a decline in middle-income neighborhoods, but this trend has varied greatly between boroughs. Some parts of the city, including portions of Brooklyn and Manhattan, have seen rapid increases in the number of upper-income neighborhoods due to gentrification and the pricing out of lower-income residents. Other boroughs, including Queens and the Bronx, have been more stable and seen less dramatic changes in their income composition, although their middle-class neighborhoods have also declined in numbers. Staten Island in many ways is the outlier, as it’s middle-class residents have grown while the number living in high-income neighborhoods.

Making predictions is always dangerous, but it certainly seems as if Manhattan will continue on it’s path towards becoming homogenously upper-income. Brooklyn has farther to go, but is being effected by many of the same forces as Manhattan. As more census data is released, it will be critical to see whether areas in Queens, the Bronx, and Staten Island begin to be affected by these same forces, or if these boroughs will remain bastions of middle-income and low-income neighborhoods. The effects of these changes in the city will continue to ripple out into the rest of the Tri-State Area, as more residents are priced out and move to other nearby cities and suburbs.

Methodology

The incomes of areas/neighborhoods were measured using census block group data, with the household median income of each block-group compared to the household median income of the New York City metropolitan area. Block-groups where the median income was less than 75% of the metropolitan area median income were defined as lower-income, 75-125% was defined as middle-income, and areas with 125% or more of the metropolitan area median income were defined as upper-income.

It is important to note that these figures represent the number of people living in each type of neighborhood, rather than the number of households that are themselves lower-income, middle-income, or upper-income. For example, 35% of New Yorkers live in middle-income areas as of 2015, which is different than saying that 35% of New Yorkers are middle-income themselves. These two concepts are strongly related, but not equivalent to each other. You could, theoretically, have an upper-income neighborhood with a large minority of lower-income residents. This neighborhood would be classified as upper-income under my system, even though a large portion of it’s residents live in poverty. Or you could have a neighborhood with roughly even proportions of lower-income, middle-income, and upper-income residents, which would make the neighborhood a middle-income neighborhood even though most of it’s population was not middle-income. However, research has shown that neighborhoods are becoming increasingly homogenous, meaning that upper-income neighborhoods have fewer and fewer poor residents, and lower-income neighborhoods have fewer and fewer rich residents (http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/files/2012/08/Rise-of-Residential-Income-Segregation-2012.2.pdf).